To prevent the gullible Baloch youth and their compatriots in other provinces from blindly following the narrative of ‘some’ Bizenjos, Mengals, Marris, Bugtis et al; become radicalised and support the bogey of Baloch liberation; and squander the golden years of life to futile militancy and insurgency; certain myths need to be busted and busted regularly and continuously. In the sinister effort to manipulate the youth of Pakistan, liberals, leftist academics and ethnic nationalists on media and in the university campuses are hand-in-glove to falsify facts, like recent diatribes of Sardar Akhtar Mengal. Three comparatively new universities, at Gwadar, Turbat and Panjgur, have particularly become breeding grounds of Baloch antagonism.

We continue the exploratory debate. Firstly, the present Balochistan was an Agency created in 1877 by the British Crown under the Treaties of Mastung (1854), Kalat (1875) and Jacobabad (1876), negotiated by Sir Robert Sandeman. So, in 1947, the area per se comprised a British protectorate called the Chief Commissioner’s Balochistan, captured by the British with Quetta as its HQs; and a tribal belt under ‘greater’ Kalat, and the states of Kharan, Labela and Makran. Then Gwadar was ruled by Oman. Sandeman established the famous tribal governance model, the ‘Sandeman System’ standing on financial inducements to Sardars in Baloch areas, and Maliks in KP/erstwhile FATA in the form of lungi and muaajib, for keeping peace in their areas. After 75 years, a bloody militancy in KP has weakened this colonial system, hence the integration of FATA as NMDs; however, continuation of the same in present-day Balochistan under political variants, has only strengthened the stranglehold of exploitative Sardars.

Kalat, a Brahui Khanate, captured by the Mirwaris (originally from Oman) in 15th Century, changed hands between Mughals and Afghans. It was part of Kandahar province in Durrani Afghanistan when British occupied it (1839). Khan of Kalat, by signing the cited treaties, lost political control outside Kalat State, and accepted British Political Agent to arbitrate intra-Baloch disputes in return for financial help and military support against Afghanistan. On creation of Agency (1877), areas under Khan of Kalat, Nawabs of Kharan & Makran and Jam of Labela were granted the status of princely states in the Royal Delhi Durbar (1903). Nawabs of Sarawan & Jhalawan were not invited to the Durbar, as their princely states were considered under the suzerainty of Kalat.

When on 11 Aug 1947, the Khan of Kalat committed to ‘negotiate’ the terms of accession to Pakistan with Jinnah, Kharan, Makran and Labela categorically rejected Kalat’s claims of suzerainty and interlocution on their behalf. Chief Commissioner’s Balochistan strongly favoured accession to Pakistan at Quetta’s Shahi Jirga after robust advocacy by Muslim League, local chapter.

Separately Kharan’s ruler Mir Habibullah Khan Nowsherwani, in his letter to Jinnah, strongly favoured joining Pakistan (independent of Kalat), lamenting delays in merger. Labela under Jam Ghulam Qadir Khan (grandfather of Jam Kamal) also wanted quick accession to Pakistan, smelling delaying tactics by the Khan. Makran under Nawab Bai Khan Gichki also insisted Jinnah to accept immediate accession of Makran to Pakistan.

Jinnah’s legal mind favoured Kalat’s historic suzerainty, while the ground sentiment was extremely pro-Pakistan and anti-Kalat due to intra-Baloch chasm and the Khan’s ‘reported’ foot-dragging for domestic political reasons. Kalat was merely one fourth of present Balochistan. The State’s nominated parliament was dominated by pro-Congress/anti Muslim League politicians of Kalat State National Party (KSNP). The KSNP leaders like Malik Saeed Khan Dehwar, Gul Khan Naseer, Alijah Ghous Bux Mengal, Ghous Bux Bizenjo, etc voted against joining Pakistan. Ahmed Yar Khan Ahmadzai, the Khan, refused to ratify this vote, as he knew independence or joining India were not feasible options. But he used the vote as leverage with Jinnah to accrue maximum advantage in the future political dispensation.

This delayed Kalat’s accession to Pakistan, and disappointed Jinnah, who eventually accepted accession requests of Kharan, Labela and Makran, independent of an isolated and landlocked Kalat. All-India Radio, on 27th March 1948, announced that Nehru had rejected Kalat’s request to join India. A humiliated Khan, consequently, announced Kalat’s accession to Pakistan. Baloch nationalists’ claim that the Khan had signed the instrument of accession at gunpoint under Pakistan Army’s pressure, and that he was arrested, are far from reality. Yes, he was arrested, but not in 1948, but on 6 Oct 1958, when he opposed Ayub Khan’s One-Unit.

Despite his hobnobbing with India, Pakistan conferred on him the royal title of Khan-e-Azam and appointed him the ceremonial head of the newly created ‘Balochistan States Union’, comprising Kharan, Makran, Labela and Kalat (1948).

Secondly, there is opposition to naming this entire area as ‘Balochistan’, since more than half is non-Baloch. According to Census-2017, Balochistan’s population is 12.34 million, which is 5.94% of Pakistan’s population. Out of this, 35.49% speak Balochi, 35.34%, speak Pashto and 17.12% are Brahui speakers, not counting the Afghans. Brahui, a Dravidian people, have lived from Lak Pass to Labela, for thousands of years, while Baloch migration from Western Arabia/Iran to this area took place around 14th/15th Century. Likewise, Kurds and Mongoloid Hazara are non-Baloch. Even Baloch tribes broadly fall in two categories – the southern half is part Baloch and part Brahui; and the ‘more’ Baloch north.

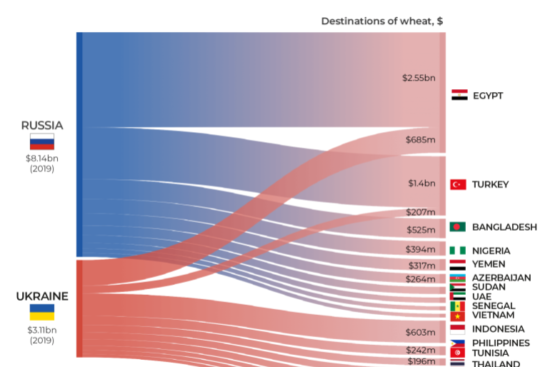

Thirdly, initial infiltration by RAW, MI-6 and others is now self-sustaining through acquired ideologies and catchy sloganeering. However, the affected population in Kalat Division, Panjgur District of Makran Division and Dera Bugti District in Sibi Division is under 3 million, with only a miniscule affected by anti-Pakistan propaganda. Like Afghanistan, Balochistan’s linkages extend and affect Iran (traditional influence, TAPI, Islamabad); GCC – UAE in particular (hydrocarbons, agriculture and Gwadar); China (Gwadar, rare earths); India (intelligence investment and anti-Pakistan opportunity); and by extension the West Plus (terrorism and narcotics threats).

Fourthly, the Pakistani state narrative in Balochistan starts and ends on development and throwing money at the problem. This approach has failed as it reinforces Sardari system, there being no alternative leadership. In the Baloch universe, Sardar’s stranglehold is almost complete, as he personifies administration, judiciary and legislature at the people’s doorstep, and not in distant cities and towns. Unlike the more egalitarian Pashtun north, Baloch citizenry is beholden to their archaic and exploitative elite with no discernable end.

We will discuss the likely antidote next week!

Leave a Reply